INTRODUCTION

31 year old Norwegian Chess GrandMaster Magnus Carlsen, the top chess player in the world, lost, in-person, to 19 year old GM Hans Mok Nieman at the Sinquefield Cup in St. Louis. As a result, Magnus abruptly withdrew from the event without explanation, refusing to complete any more games in the tournament. Since then, Carlsen has formally accused Niemann of cheating on social media platforms.

Hans Nieman has been in the spotlight online due to his character being rare and rather undignified for the chess world.

Chess.com investigated and found that Hans has likely cheated in more than 100 online chess games on their website and published their findings in a long report and banned him from their website.

https://www.chess.com/blog/CHESScom/hans-niemann-report

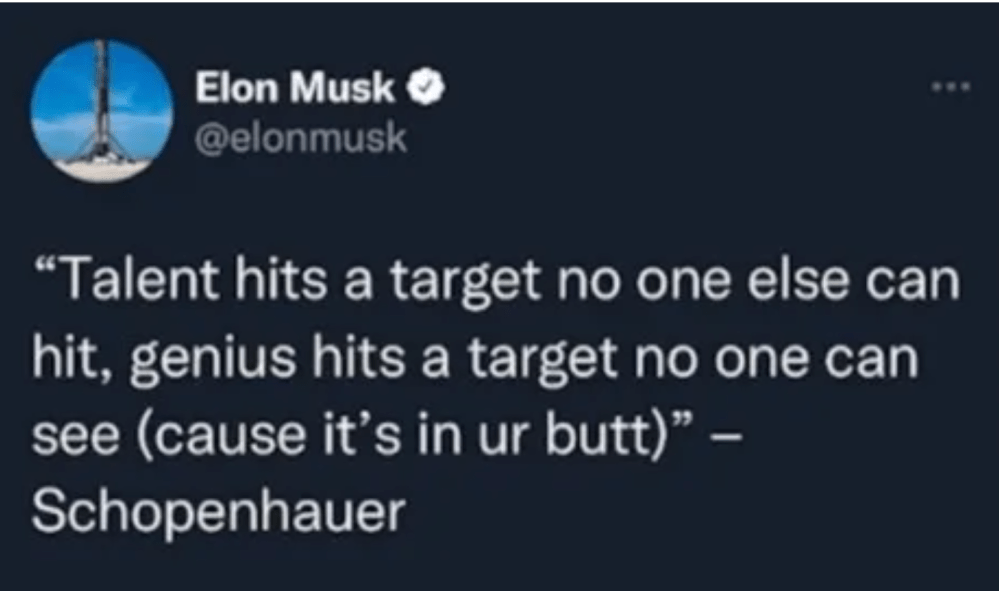

Hikaru Nakamura is included in the lawsuit for allegedly publishing hours of video content, “…attempting to bolster Carlsen’s false cheating allegations…with numerous additional defamatory statements.” The complaint mentions that Hikaru “alluded” to Carlsen cheating but supplied no direct video quotes or evidence. Hans Nieman has admitted to cheating on Chess.com when younger, but denies cheating in the Sinquefield cup or at any money prize tournament, online or in-person. The chess drama culminated in a false and ridiculous rumor that Hans Mok Nieman cheated using vibrating Morse code anal beads, which even Elon Musk commented about on Twitter.

If interested in learning whether cheating in chess with vibrating anal beads and Python is theoretically possible, I discuss that in a separate article:

https://gaveltech.net/2023/02/05/morse-code-anal-beads/

Nieman has now sued Magnus, Hikaru, and Chess.com in a 100 million lawsuit (which is an amount that has no basis in reality probably, other than to make headlines and get Hans Nieman attention). We will examine three aspects of the case: defamation, Sherman Antitrust, and Tortious Interference to see if these claims have any teeth.

DEFAMATION

Proving defamation requires that the following elements be met:

- A false statement purporting to be fact;

- Publication or communication of that statement to a third person;

- Fault amounting to at least negligence; and

- Damages, or some harm caused to the reputation of the person or entity who is the subject of the statement. Must be proven with a preponderance of evidence standard

The famous The New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) case differentiates between the treatment of a plaintiff who is a “public figure” versus a plaintiff who is a “private figure.” A public figure is subject to a heightened actual malice standard – by clear and convincing evidence, rather than a preponderance, the Plaintiff must prove that the defendant’s statements were made with knowledge of being false or reckless disregard for truth or falsity.

Nieman’s fame and notoriety may mean that he is classified as a public figure, rather than a private figure, if he has thrust himself into the spotlight, and should therefore expect more criticism than a private figure. In other words, it would make his lawsuit harder. The complaint itself actually makes it seem like Hans Nieman is a public figure, funnily enough, describing him as a sort of legendary chess “prodigy.” If a household name standard applies, the court may not consider Hans Nieman to be a household name in the way Magnus Carlsen likely is. First, let us assume Hans Nieman is a public figure not subject to a higher standard.

Hans Nieman is suing both for Slander (verbal) and libel (written).

Defamation is only actionable if the plaintiff makes a false statement purporting to be fact. Opinions cannot be defamatory since they merely express commentary based on public information and do not purport to be fact. Also, the statement must be capable of being proven true or false. Here, it is likely that a court would not interpret defendants’ claims to be anything other than opinion. Magnus’ statement may be considered a wrong opinion based on observation. Moreover, it is questionable whether any statement made can actually be shown to be true or false since we do not know if Hans Nieman cheated. If cheating allegations are proven to be true, Magnus’ statements, for instance, would be true statements; it would be ridiculous for Hans Nieman to claim that Magnus thought Hans nieman did not cheat when Magnus said that Hans did cheat.

Recall, if Nieman is considered to be a public figure, he must show by clear and convincing evidence that Magnus, for instance, accused him of cheating with false knowledge or a reckless disregard for truth or falsity. Of course, he likely cannot show Magnus had false knowledge; it seems it seems Magnus genuinely believed his own statements. In this scenario, a reckless standard applies – the statement must shown to be reckless. But remember that the statement still must be a false statement purporting as fact, not an opinion – and not even that standard is likely met.

Another good argument against Hans that makes the above analysis unnecessary should be pointed out. Professor of law at Yale University, Steven l. Carter points out that lawsuits by individuals accused of cheating at games have a, “mixed but mostly rocky history” Hans Niemann’s $100 Million Chess Lawsuit Will Be Tough to Win.

He points out that Courts are often unwilling to second guess a gaming organization’s own findings of wrongdoing. This means that since the International Chess Federation generally feels Hans cheated, the court may actually refer to that and state that they agree the allegations are true – and if they are considered true, there can be no defamation.

SHERMAN ANTITRUST

Article I section 8 clause of the U.S. Constitution, the commerce clause, grants Congress the power to “regulate commerce. . . among the several states.” Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 is grounded in the commerce clause, prohibiting activities that restrict interstate commerce, like economic monopolies.

Winning an Antitrust case would be difficult if not even the defamation claim can be won. Convincing a jury that the defendants actually entered into an agreement would be difficult if there is no actual written agreement or recorded communication between defendants. Defendants doing similar things at same time, based on believing that Hans Nieman cheated, is not a restraint of trade agreement. The elements of a Sherman violation are also met if there is a conspiracy. Here a conspiracy is also unlikely; a conspiracy is an agreement, possibly oral, to commit an illegal act; usually this pertains to conspiracy to commit fraud. It is difficult to say the defendants are working together to perform an illegal act. If the case is not dismissed, Nieman would want to see all the communications between the parties.

TORTIOUS INTERFERENCE

There are two types of tortious interference: tortious interference with contract and tortious interference with prospective economic advantage.

Tortious interference with a contract occurs when someone improperly induces a breach of contract.

In the case at hand, it seems relatively clear there is no prospective economic advantage to be gained by banning Hans Nieman from Chess.com or tournaments – and even if there is, it seems clear that the reason for the ban and alleged defamation was not to win some economic advantage. For tortious interference with contract, like the Sherman antitrust claim, the Plaintiff needs to prove the defendants worked together in agreement for the purpose to do bad to Nieman.

To prove tortious interference, one must show “the defendant’s conduct led to a breach of the contract.” This is not likely the case; chess.com conducted an investigation and found that Hans Nieman cheating in chess when using their website. Although chess.com initially conducted the investigation and had evidence against Han prior to the incident, but did not use it, I would argue that it was the plaintiffs conduct that led to Chess.com banning Hans Nieman rather than Magnus’ conduct; moreover, Magnus did not intentionally interfere, and intent is necessary in tortious interference. Again, if case is not dismissed Nieman would want to see all the communications between the parties.

Leave a comment